The delicate question of whether customary land in Teso should be used as collateral for bank loans has once again taken center stage, following the release of a groundbreaking survey by the Land and Equity Movement in Uganda (LEMU) and its partners.

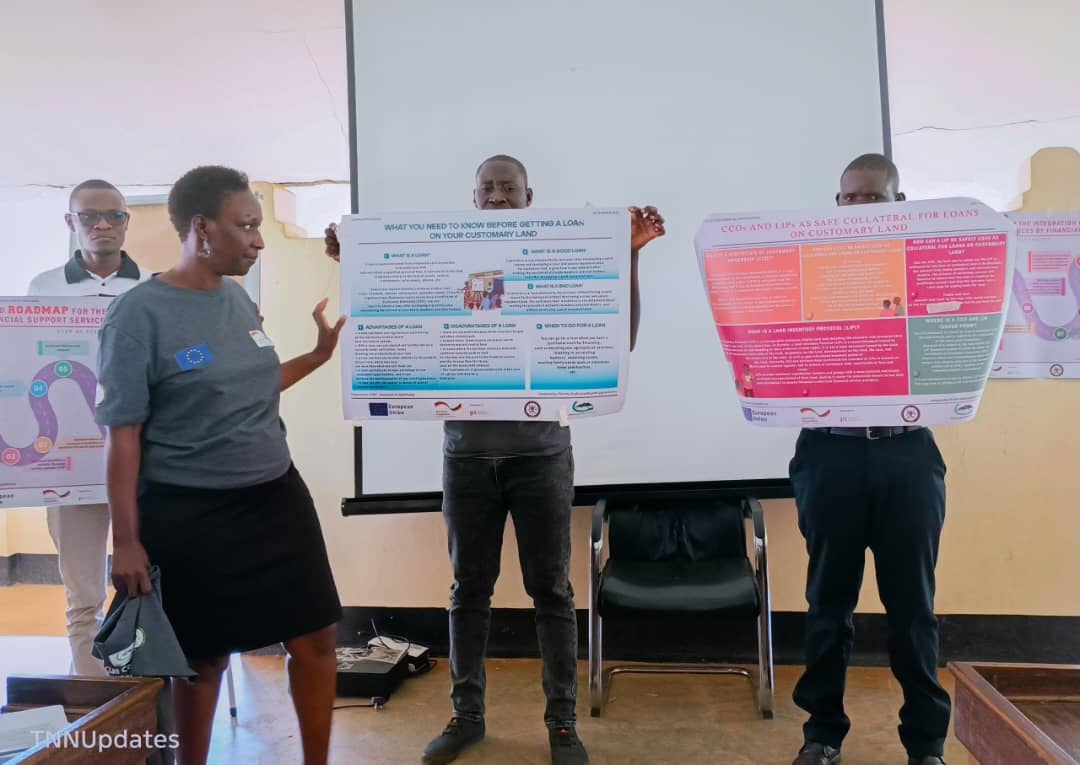

The study, presented during a Regional Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue on the use of customary land documents in Soroti District on October 3, 2025, revealed that while more than 8,000 customary land titles (Certificates of Customary Ownership – CCOs and Land Inventory Protocols – LIPs) have been issued in the region, families and clans remain deeply divided on whether such land should be risked in pursuit of credit.

According to LEMU’s Executive Director, Dr. Theresa Auma, the research confirmed that communities regard land as a shared heritage rather than an individual asset, making it difficult for families to agree to pledge land for loans.

“Our findings show that the consent required from family and clan members is not a formality but a deeply embedded safeguard,” Dr. Auma explained.

“In most cases, families do not agree to give land for loans, which reflects both cultural values and fears of losing ancestral property.”

The survey, conducted across districts of Soroti, Katakwi in Teso sub-region, and Dokolo in Lango Sub Region sought to understand the extent to which communities use CCOs and LIPs as collateral for credit and why adoption has remained very low despite government and donor efforts to promote land documentation.

Hindrances to Using CCOs and LIPs as Collateral

The report, titled “Family & Clan Consent is Important Before Using Customary Land for Any Loan,” highlighted a series of reasons why communities have resisted using their CCOs and LIPs to access bank loans.

Among the major obstacles were:

- Loans not a key reason for land registration – Many households viewed land registration as a way to secure tenure and reduce disputes, not as a pathway to credit.

- Low demand for loans – In many villages, there is minimal appetite for formal loans, with households relying on subsistence farming or informal savings groups.

- Financial institutions’ preferences – Banks often prefer freehold or leasehold land titles instead of customary documents.

- Lack of awareness – Many people did not know that CCOs and LIPs could serve as collateral.

- Distrust of financial institutions – There is widespread fear that banks may retain original documents even after repayment.

- Delays and bureaucracy – Lengthy processes in obtaining CCOs/LIPs discouraged interest.

- Fear of loan default – Communities worried about what would happen if crops failed or incomes dropped, especially in the absence of agricultural insurance.

- Cultural and gender barriers – In some families, women were excluded from decision-making on land, limiting their ability to access credit.

- Alternative sources of credit – Households preferred Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs), which were more flexible and accessible.

- Complex bank conditions – Complicated loan terms and conditions often went unread or misunderstood.

- Unclear government messaging – Agencies like GIZ initially emphasized land tenure security over credit use, which shaped perceptions.

- Religion and cultural prohibitions – Some religious and clan leaders opposed pledging land for financial ventures.

Dr. Auma summarized: “The reality is that while CCOs and LIPs have provided tenure security, their use as collateral is still far from being embraced. Families view land as too important to be risked, and financial institutions have not done enough to build trust.”

Community Recommendations

The study’s findings were accompanied by a set of community-driven recommendations aimed at bridging the gap between land tenure reforms and financial inclusion.

Among them were:

- Financial institutions should assist applicants in developing viable business plans before loans are issued.

- No loans should be granted where families are in conflict over land.

- Loans should be disbursed in installments to reduce risks of misuse.

- Loan officers should visit families and engage them directly about loan conditions.

- Banks should always acknowledge receipt of original land documents to build trust.

- Money lenders should be barred from charging accumulated compound interest.

- Financial institutions must recognize the central role of clans and families in consent processes.

- Loan approvals should consider the actual capacity of households to repay.

- Smallholder farmers should receive fair interest rates tailored to their realities.

- New loan products should be developed that do not require land as collateral.

- Government should regulate and monitor the work of financial institutions, including money lenders.

- Loans should only be granted for purposes clearly stated in applications.

- Banks must follow up on implementation of loans rather than waiting for repayment deadlines.

Financial Institutions’ Concerns

On their part, financial service providers (FSPs) acknowledged the challenges but also pointed to systemic issues that have prevented them from embracing customary land titles.

Their main hindrances included:

- Limited knowledge of CCOs/LIPs among both bank staff and clients.

- Absence of regulatory guidelines from the Bank of Uganda (BoU) and the Uganda Microfinance Regulatory Authority (UMRA) on how CCOs should be used as collateral.

- Complexity of family and clan consent, which prolongs loan processing and increases risks.

- Frequent intra-family and intra-clan conflicts around land.

- Multiple ownership of customary land, which complicates collateral assessment.

Some proposed masterclass-style awareness sessions by LEMU and GIZ, targeting both communities and regulators.

Others suggested that large family CCOs could be subdivided into smaller units for individuals, while collective CCOs could be restricted to large-scale family or clan projects.

A financial officer who attended the meeting, but requested anonymity, admitted:

“CCOs can be valuable, but the challenge is consent. If one family member objects, the loan stalls. That is why most banks avoid them, unless communities themselves resolve disputes beforehand.”

Voices from Stakeholders

The event attracted local leaders, government representatives, financial institutions, money lenders, and civil society actors.

Their reactions underscored the urgency of finding a balance between land security and credit access.

Sam Eriaku, Deputy Team Leader of GIZ RELAPU, noted that over 8,000 land titles have already been issued in Teso.

He emphasized that the original goal was to end land conflicts by demarcating boundaries, not necessarily to promote loans.

Still, he urged financial institutions to use land titles wisely when assessing creditworthiness.

Hajji Imran Muluga, the Soroti Resident District Commissioner (RDC), praised GIZ and LEMU for helping communities formalize land ownership.

“Land is gold,” he said. “We must use it productively, but also cautiously. I call on the people of Teso to see land as an asset for wealth creation, not just heritage.”

Moses Esatu, Principal Assistant Secretary Soroti District, warned that misuse of loans acquired through land titles could lead to loss of land.

“We already see cases where people mortgage their land and fail to repay,” he said. “This survey is timely. It reminds us that education on responsible land use is critical.”

Oyuru Anthony, Soroti District LCV Councilor, highlighted the risks of natural disasters and crop failures.

He noted that without crop insurance, many farmers defaulted, leading to land loss.

Robert Ewangu, a money lender, admitted there was a need for stronger regulation.

“The Bank of Uganda and UMRA must regulate loan interest rates and ensure fairness. Communities should not be exploited,” he said.

Moses Emogu Eroju, LCIII Chairperson Katine Sub County, reassured cultural institutions that banks could not grab land without clan consent.

“It is clear now that banks cannot take land without the involvement of cultural leaders. That safeguard should give our people confidence,” he noted.

Lawyer Elasu Edmond who is also member of Soroti City Land board and also Soroti City Mayoral Candidate called for reducing bank agreements into local languages so communities could understand what they were signing.

He stressed that consent should not be treated lightly.

“This land is customary. The law protects the illiterate. If consent is not clear, then families risk being dispossessed,” he said.

Gender and Consent Issues

The survey also revealed significant gender dimensions.

Women, who play a key role in agriculture, are often sidelined in land decisions.

Customary norms still vest control of land in male heads of families or clans, limiting women’s ability to use CCOs for loans.

Dr. Auma emphasized that financial institutions and policymakers must integrate gender-sensitive approaches in their programs.

“If women are excluded from decisions, then half of the productive population is being locked out of opportunities. Consent must mean inclusive consent,” she said.

Customary land accounts for over 70% of land tenure in Uganda. In regions like Teso and Lango, where ancestral land is central to identity and livelihoods, reform efforts face unique cultural and practical barriers.

However, without regulatory clarity from the Bank of Uganda and UMRA, banks remain reluctant to risk lending against customary titles. Similarly, without robust financial literacy, communities remain hesitant to use CCOs beyond tenure security.

As RDC Imran Muluga reminded the gathering: “Land is gold. But gold can either enrich you or ruin you, depending on how you use it. Let us use it wisely.”

For advertising or to run your news article, contact us on 0785674642 or email tesonewsnetwork@gmail.com